Detentions for mental health treatment in Scotland 2021-22 – new report

Publication date: 3 Nov, 2022

A new report from the Mental Welfare Commission shows a 2.3% drop in numbers of times people were detained in hospital against their will for mental health treatment in Scotland in 2021-22 compared to the previous year.

While the Commission welcomed the slight drop in overall detentions (to 6,569), it should be seen against a 10.5% rise in the previous year – which was double the rate of increase seen year on year in recent times.

The Commission has a duty to monitor and report on the use of the Mental Health Act. There are three different ways people can be detained under the Act - either by emergency detention, short term detention, or through a compulsory treatment order.

Areas of concern for the Commission include:

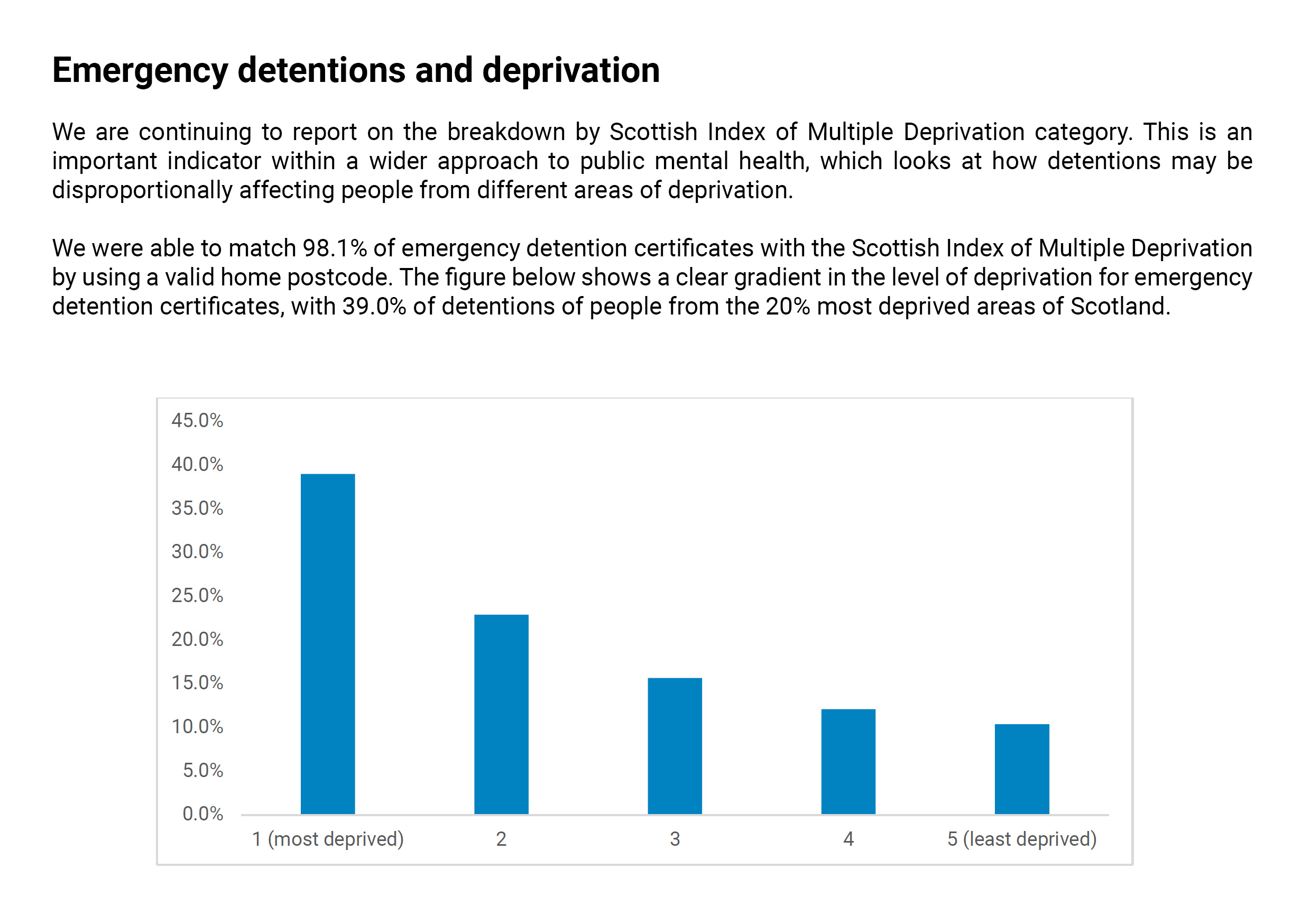

Deprivation

The report shows a clear association between mental ill health and social deprivation , with 39% of all emergency detentions happening to people from the 20% most deprived areas of Scotland.

Lack of safeguarding

The Commission again raises concerns over the lack of consent from a mental health officer (a specialist social worker) when emergency detentions take place. In 2021-22 this was at its lowest level in 10 years: only 40.5% of these detentions involved mental health officers, and in one health board area – Greater Glasgow and Clyde – the figure dropped to only 22%.

Dr Arun Chopra, medical director, Mental Welfare Commission, said:

“When people become very unwell with mental ill health, some aspects of their care and treatment may need to be delivered against their will, to ensure their safety and wellbeing. All such use of compulsion must be done using the Mental Health Act, the compulsory care should last for the shortest possible length of time, and must be reported to the Mental Welfare Commission.

“We remain concerned over the way emergency detentions are taking place. Consent of a mental health officer (MHO) is an important safeguard and should happen every time a person is detained using the Act. For emergency detentions, consent from an MHO has fallen below half for all such detentions for the last two years in succession, with considerable variations in different parts of Scotland. This is not acceptable; people should receive this safeguard, where practicable, no matter where they live in the country.

“Last year was the first time that we were able to use post-code data to clarify the links between areas with greater deprivation and mental ill health requiring the use compulsion. This year we have extended this so that the links are clearer.

“We hope this data will be used by government as it considers its response to the recently published Scottish Mental Health Law Review, which is seeking major changes to Scotland’s laws in this area for the future.”